Gaul

Gaul (Latin: Gallia) is a historical name used in the context of Ancient Rome in references to the region of Western Europe approximating present day France, Luxembourg and Belgium, most of Switzerland, the western part of Northern Italy, as well as the parts of the Netherlands and Germany on the left bank of the Rhine.

The Gauls were the speakers of the Gaulish language (an early variety of Celtic) native to Gaul. According to the testimony of Julius Caesar, the Gaulish language proper was distinct from the Aquitanian language and the Belgic language[1]. Archaeologically, the Gauls were bearers of the La Tène culture, which extended across all of Gaul, as well as east to Rhaetia, Noricum, Pannonia and southwestern Germania.

Gauls under Brennus defeated Roman forces in a battle circa 390 BC. The peak of Gaulish expansion was reached in the 3rd century BC, in the wake of the Gallic invasion of the Balkans of 281-279 BC, Gaulish settlers moved as far afield as Asia Minor.[2]

During the 2nd and 1st century BC, Gaul fell under Roman rule. Gallia Cisalpina was conquered in 203 BC, Gallia Narbonensis in 123 BC. Gaul was invaded by the Cimbri and the Teutons after 120 BC, who were in turn defeated by the Romans by 101 BC. Julius Caesar finally subdued the remaining parts of Gaul in his campaigns of 58 to 51 BC. Roman control of Gaul lasted for five centuries, until the last Roman rump state, the Domain of Soissons, fell to the Franks in AD 486. During this time, The Celtic culture had become amalgamated into a Gallo-Roman culture and the Gaulish language was likely extinct by the 6th century.

Contents |

Name

The names Gallia and Galatia are of uncertain origin, either from a native name of a tribe, or exonyms. Birkhan (1997) considers a root * g(h)al- "powerful" (PIE * gelh, well-attested in Celtic, and with cognates in Balto-Slavic), but speculates that the name also could be taken from a Gallos River, comparable to the names of the Volcae and the Sequani which are likely derived from hydronyms. There also have been attempts to trace Keltoi and Galatai to a single origin. It is most likely that the terms originated as names of minor tribes * Kel-to and/or Gal(a)-to- which were the earliest to come into contact with the Roman world, but which have disappeared without leaving a historical record.[3] The name is sometimes linked to the ethnic name Gael, which is, however, derived from Old Irish Goidel (derived, in turn, from Old Welsh Guoidel "Irishman", now spelled Gwyddel, from a Brittonic root *Wēdelos meaning literally "forest person, wild man"[4]), and cannot be directly related.

Josephus claimed that the Gauls were descended from Gomer, the grandson of Noah. Hellenistic etiology connects the name with Galatia (first attested by Timaeus of Tauromenion in the 4th c. BC), and it was suggested that the association was inspired by the "milk-white" skin (γάλα, gala, "milk") of the Gauls (Greek: Γαλάται, Galatai, Galatae).

The English Gaul and French French: Gaule, Gaulois in spite of superficial similarity are unrelated to Latin Gallia, Galli. They are rather derived from the Germanic term walha, an exonym applied by Germanic speakers to Celts, likely via a Latinization of Frankish *Walholant "Gaul", literally "Land of the Foreigners/Romans", making it partially cognate with the name Wales), the usual word for the non-Germanic-speaking peoples (Celtic-speaking and Latin-speaking indiscriminately).[5]

History

Pre-Roman Gaul

The early history of the Gauls is predominantly a work in archaeology - there being little written information (save perhaps what can be gleaned from coins) concerning the peoples that inhabited these regions - and the relationships between their material culture, genetic relationships (the study of which has been aided, in recent years, through the field of archaeogenetics), and linguistic divisions rarely coincide.

The major source of materials on the Celts of Gaul was Poseidonios of Apamea, whose writings were quoted by Timagenes, Julius Caesar, the Sicilian Greek Diodorus Siculus, and the Greek geographer Strabo.[6]

Many cultural traits of the early Celts seem to have been carried northwest up the Danube Valley, although this issue is contested. It seems as if they derived many of their skills (like metal-working), as well as certain facets of their culture, from Balkan peoples. Some scholars think that the Bronze Age Urnfield culture represents an origin for the Celts as a distinct cultural branch of the Indo-European-speaking peoples (see Proto-Celtic). The Urnfield culture was preeminent in central Europe during the late Bronze Age, from ca. 1200 BC until 700 BC. The spread of iron-working led to the development of the Hallstatt culture (ca. 700 to 500 BC) directly from the Urnfield. Proto-Celtic, the latest common ancestor of all known Celtic languages, is considered by some scholars to have been spoken at the time of the late Urnfield or early Hallstatt cultures.

The Hallstatt culture was succeeded by the La Tène culture, which developed out of the Hallstatt culture without any definite cultural break, under the impetus of considerable Mediterranean influence from the Greek, Phoenician, and Etruscan civilizations. The La Tène culture developed and flourished during the late Iron Age (from 450 BC to the Roman conquest in the 1st century BC) in France, Switzerland, Austria, southwest Germany, Bohemia, Moravia, Slovakia and Hungary. Farther north extended the contemporary Pre-Roman Iron Age culture of northern Germany and Scandinavia.

By the 2nd century BC, France was called Gaul (Gallia Transalpina) by the Romans. In his Gallic Wars, Julius Caesar distinguishes among three ethnic groups in Gaul: the Belgae in the north (roughly between Rhine and Seine), the Celts in the center and in Armorica, and the Aquitani in the southwest, the southeast being already colonized by the Romans. While some scholars believe that the Belgae south of the Somme were a mixture of Celtic and Germanic elements, their ethnic affiliations have not been definitively resolved. One of the reasons is political interference upon the French historical interpretation during the 19th century. French historians adopted fully the explanation of Caesar who stated that Gaul stretched from the Pyrenees up to the Rhine in the north. This fitted the French expansionist aspirations of the time under Napoleon III. In the north of (modern) France, the Gaul-German language border was situated somewhere between the Seine and the Somme. Northern Belgic tribes like the Nervians, Atrebates or Morini appear to be Germanic tribes who migrated from the Germanic hinterland and adopted Celtic language and customs , as all of the names of their leaders and towns are Celtic. In addition to the Gauls, there were other peoples living in Gaul, such as the Greeks and Phoenicians who had established outposts such as Massilia (present-day Marseille) along the Mediterranean coast. Also, along the southeastern Mediterranean coast, the Ligures had merged with the Celts to form a Celto-Ligurian culture.

In the 2nd century BC, Mediterranean Gaul had an extensive urban fabric and was prosperous, while the heavily forested northern Gaul had almost no cities outside of fortified compounds (or oppida) used in times of war. The prosperity of Mediterranean Gaul encouraged Rome to respond to pleas for assistance from the inhabitants of Massilia, who were under attack by a coalition of Ligures and Gauls. The Romans intervened in Gaul in 125 BC, and by 121 BC they had conquered the Mediterranean region called Provincia (later named Gallia Narbonensis). This conquest upset the ascendancy of the Gaulish Arverni tribe.

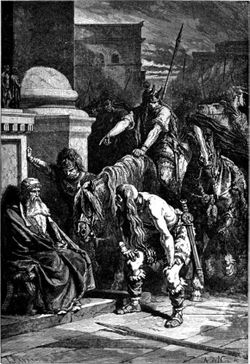

Conquest by Rome

The Roman proconsul and general Julius Caesar pushed his army into Gaul in 58 BC, on the pretext of assisting Rome's Gaullish allies against the migrating Helvetii. With the help of various Gallic tribes (for example, the Aedui) he managed to conquer nearly all of Gaul. But the Arverni tribe, under Chieftain Vercingetorix, still defied Roman rule. Julius Caesar was checked by Vercingetorix at a siege of Gergorvia, a fortified town in the center of Gaul. Caesar's alliances with many Gallic tribes broke. Even the Aedui, their most faithful supporters, threw in their lot with the Arverni but the ever loyal Remi (best known for its cavalry) and Lingones sent troops to support Caesar. The Germans of the Ubii also sent cavalry which Caesar equipped with Remi horses. Caesar captured Vercingetorix in the Battle of Alesia, which ended the majority of Gallic resistance to Rome.

As many as a million people (probably 1 in 5 of the Gauls) died, another million were enslaved, 300 tribes were subjugated and 800 cities were destroyed during the Gallic Wars. The entire population of the city of Avaricum (Bourges) (40,000 in all) were slaughtered.[7] During Julius Caesar's campaign against the Helvetii (present-day Switzerland) approximately 60% of the tribe was destroyed, and another 20% was taken into slavery.

Roman Gallia

The Gaulish culture then was massively submerged by Roman culture, Latin was adopted by the Gauls, Gaul, or Gallia, was absorbed into the Roman Empire, all the administration changed and Gauls eventually became Roman citizens.[8] From the 3rd to 5th centuries, Gaul was exposed to raids by the Franks. The Gallic Empire broke away from Rome from 260 to 273, consisting of the provinces of Gaul, Britannia, and Hispania, including the peaceful Baetica in the south.

Following the Frankish victory at the Battle of Soissons in AD 486, Gaul (except for Septimania) came under the rule of the Merovingians, the first kings of France. Gallo-Roman culture, the Romanized culture of Gaul under the rule of the Roman Empire, persisted particularly in the areas of Gallia Narbonensis that developed into Occitania, Gallia Cisalpina and to a lesser degree, Aquitania. The formerly Romanized north of Gaul, once it had been occupied by the Franks, would develop into Merovingian culture instead. Roman life, centered on the public events and cultural responsibilities of urban life in the res publica and the sometimes luxurious life of the self-sufficient rural villa system, took longer to collapse in the Gallo-Roman regions, where the Visigoths largely inherited the status quo in the early 5th century. Gallo-Roman language persisted in the northeast into the Silva Carbonaria that formed an effective cultural barrier with the Franks to the north and east, and in the northwest to the lower valley of the Loire, where Gallo-Roman culture interfaced with Frankish culture in a city like Tours and in the person of that Gallo-Roman bishop confronted with Merovingian royals, Gregory of Tours.

The Gauls

Social structure and tribes

The Druids were not the only political force in Gaul, however, and the early political system was complex, if ultimately fatal to the society as a whole. The fundamental unit of Gallic politics was the tribe, which itself consisted of one or more of what Caesar called "pagi". Each tribe had a council of elders, and initially a king. Later, the executive was an annually-elected magistrate. Among the Aedui, a tribe of Gaul, the executive held the title of "Vergobret", a position much like a king, but its powers were held in check by rules laid down by the council.

The tribal groups, or pagi as the Romans called them (singular: pagus; the French word pays, "region", comes from this term) were organized into larger super-tribal groups that the Romans called civitates. These administrative groupings would be taken over by the Romans in their system of local control, and these civitates would also be the basis of France's eventual division into ecclesiastical bishoprics and dioceses, which would remain in place - with slight changes — until the French Revolution.

Although the tribes were moderately stable political entities, Gaul as a whole tended to be politically-divided, there being virtually no unity among the various tribes. Only during particularly trying times, such as the invasion of Caesar, could the Gauls unite under a single leader like Vercingetorix. Even then, however, the faction lines were clear.

The Romans divided Gaul broadly into Provincia (the conquered area around the Mediterranean), and the northern Gallia Comata ("free Gaul" or "long haired Gaul"). Caesar divided the people of Gaulia Comata into three broad groups: the Aquitani; Galli (who in their own language were called Celtae); and Belgae. In the modern sense, Gaulish tribes are defined linguistically, as speakers of dialects of the Gaulish language. While the Aquitani were probably Vascons, the Belgae would thus probably be counted among the Gaulish tribes, perhaps with Germanic elements.

Julius Caesar, in his book, Commentarii de Bello Gallico, comments:

All Gaul is divided into three parts, one of which the Belgae inhabit, the Aquitani another, those who in their own language are called Celts, in ours Gauls, the third. All these differ from each other in language, customs and laws. The Garonne River separates the Gauls from the Aquitani; the River Marne and the River Seine separate them from the Belgae. Of all these, the Belgae are the bravest, because they are furthest from the civilisation and refinement of (our) Province, and merchants least frequently resort to them, and import those things which tend to effeminate the mind; and they are the nearest to the Germani, who dwell beyond the Rhine, with whom they are continually waging war; for which reason the Helvetii also surpass the rest of the Gauls in valour, as they contend with the Germani in almost daily battles, when they either repel them from their own territories, or themselves wage war on their frontiers. One part of these, which it has been said that the Gauls occupy, takes its beginning at the River Rhone; it is bounded by the Garonne River, the Atlantic Ocean, and the territories of the Belgae; it borders, too, on the side of the Sequani and the Helvetii, upon the River Rhine, and stretches toward the north. The Belgae rises from the extreme frontier of Gaul, extend to the lower part of the River Rhine; and look toward the north and the rising sun. Aquitania extends from the Garonne to the Pyrenees and to that part of the Atlantic (Bay of Biscay) which is near Spain: it looks between the setting of the sun, and the north star.

Religion

The Gauls practiced a form of animism, ascribing human characteristics to lakes, streams, mountains, and other natural features and granting them a quasi-divine status. Also, worship of animals was not uncommon; the animal most sacred to the Gauls was the boar, which can be found on many Gallic military standards, much like the Roman eagle.

Their system of gods and goddesses was loose, there being certain deities which virtually every Gallic person worshiped, as well as tribal and household gods. Many of the major gods were related to Greek gods; the primary god worshiped at the time of the arrival of Caesar was Teutates, the Gallic equivalent of Mercury. The "father god" in Gallic worship was "Dis Pater" (cf. Dyaus Pitar), who could be assigned the Roman name "Saturn". However there was no real known theology, just a set of related and evolving traditions of worship.

Perhaps the most intriguing facet of Gallic religion is the practice of the Druids. The druids presided over human or animal sacrifices that were made in wooded groves or rude temples. They also appear to have held the responsibility for preserving the annual agricultural calendar and instigating seasonal festivals which corresponding to key points of the lunar-solar calendar. The religious practices of druids were syncretic and borrowed from earlier pagan traditions, especially of ancient Britain. Julius Caesar mentions in his Gallic Wars that those Celts who wanted to make a close study of druidism went to Britain to do so. In a little over a century later, Gnaeus Julius Agricola mentions Roman armies attacking a large druid sanctuary in Anglesey, also known as Holyhead, Wales. There is no certainty concerning the origin of the druids, but it is clear that they vehemently guarded the secrets of their order and held sway over the people of Gaul. Indeed they claimed the right to determine questions of war and peace, and thereby held an "international" status. In addition, the Druids monitored the religion of ordinary Gauls and were in charge of educating the aristocracy. They also practiced a form of excommunication from the assembly of worshipers, which in ancient Gaul meant a separation from secular society as well. Thus the Druids were an important part of Gallic society. The nearly complete and mysterious disappearance of the Celtic language from most of the territorial lands of ancient Gaul, with the exception of Brittany, France, can be attributed to the fact that Celtic druids refused to allow the Celtic oral literature or traditional wisdom to be committed to the written letter.

The Celts practiced headhunting as the head was believed to house a person's soul. Ancient Romans and Greeks recorded the Celts' habits of nailing heads of personal enemies to walls or dangling them from the necks of horses.[9]

See also

- Ambiorix

- Asterix - a French comic about Gaul and Rome set in 40s BC

- Bog body

- Braccae - trousers, typical Gallic dress

- Cisalpine Gaul

- Galatia

- Gallo-Roman culture

- Gaulish language

- Gauls

- Lugdunum

- Roman Republic

- Roman Gaul

- Gallia Narbonensis

- Vercingetorix

- Travian

References

- Birkhan, H. (1997). Die Kelten. Vienna.

Footnotes

- ↑ "All Gaul is divided into three parts, one of which the Belgae inhabit, the Aquitani another, those who in their own language are called Celtae, in our Galli, the third. All these differ from each other in language, customs and laws." Gallia est omnis divisa in partes tres, quarum unam incolunt Belgae, aliam Aquitani, tertiam qui ipsorum lingua Celtae, nostra Galli appellantur. Hi omnes lingua, institutis, legibus inter se differunt. Gallos ab Aquitanis Garumna flumen. (Julius Caesar, De bello Gallico, T. Rice Holmes, Ed., 1.1

CAESARIS COMMENTARIORVM DE BELLO GALLICO (in Latin) - ↑ Pausanias, Description of Greece, Phocis

- ↑ Birkhan 1997:48.

- ↑ Koch, John, "Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia", ABC-CLIO, 2006, pp. 775-6

- ↑ Sjögren, Albert, "Le nom de "Gaule", in "Studia Neophilologica", Vol. 11 (1938/39) pp. 210-214.> The Germanic w is regularly rendered as gu / g in French (cf. guerre = war, garder = ward), and the diphthong au is the regular outcome of al before a following consonant (cf. cheval ~ chevaux). Gaule or Gaulle can hardly be derived from Latin Gallia, since g would become j before a (cf. gamba > jambe), and the diphthong au would be incomprehensible; the regular outcome of Latin Gallia is Jaille in French which is found in several western placenames. Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology (OUP 1966), p. 391. Nouveau dictionnaire étymologique et historique (Larousse 1990), p. 336.

- ↑ Berresford Ellis, Peter (1998). The Celts: A History. Caroll & Graf. pp. 49–50. ISBN 0-786-71211-2.

- ↑ Julius Caesar The Conquest of Gaul

- ↑ Helvetti

- ↑ see e.g. Diodorus Siculus, 5.2

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||